Westchester Housewife

Meet Debra Burlingame, who won a battle at Ground Zero.

BY TUNKU VARADARAJAN

Saturday, October 1, 2005 12:01 p.m. EDT

Rage renders some people incoherent and others blind. It causes some to flare up--fiercely, but briefly--and then to burn out. In others, it does no more than instill sadness, and paralysis. Yet in Debra Burlingame--the 51-year-old sister of Charles F. "Chic" Burlingame, the pilot of the plane that was crashed into the Pentagon by terrorists on September 11, 2001--rage has fueled eloquence, an impressively mulish obstinacy, and an almost eerie moral clarity.

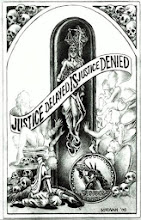

These are not all virtues, however, if you happen to be--like the founders and planners of the International Freedom Center--the object of that rage. Just this week, George Pataki, New York's governor, ordered the ousting of the Freedom Center from the World Trade Center memorial site: He did so, it should be said, in response to the relentless pressure exerted by Ms. Burlingame and the Take Back the Memorial Movement, a coalition of little platoons of 9/11 family members assembled to boot the Freedom Center off Ground Zero. This is ground that Ms. Burlingame and numerous Americans regard as hallowed; for them, the Freedom Center's apparent mission--the establishment of an educational venue focused more squarely on such matters as the Native American genocide and the Jim Crow South than on the victims and perpetrators of 9/11--was pure anathema, proof not merely of leftist muddle-headedness but also of an elitist contempt for popular feeling.

The Take Back the Memorial Movement's best-known voice--and certainly the most articulate critic of the Freedom Center--is Ms. Burlingame, who started it all on these pages in early June, when she wrote an op-ed essay titled "The Great Ground Zero Heist." In it, she made public the Freedom Center's determination to build a memorial that "stubbornly refuses to acknowledge" 9/11.

"Rather than a respectful tribute to our individual and collective loss," she wrote, "[we] will get a slanted history lesson, a didactic lecture on the meaning of liberty in a post-9/11 world . . . [and] a heaping foreign policy discussion over the greater meaning of Abu Ghraib and what it portends for the country and the rest of the world." She also asked whether it was seemly for the Freedom Center's advisory board to include members who had said, "I'm not sure which is more frightening: the horror that engulfed New York City or the apocalyptic rhetoric emanating daily from the White House" (Columbia's Eric Foner); pushed for the center to highlight how 9/11 had led to the curtailment of civil liberties (the ACLU's Anthony Romero); and led a world-wide "Stop Torture Now" campaign focused on the U.S. military (Michael Posner, of Human Rights First).

Her rage was irrefutable, and one got the sense, after her piece appeared in print, that the Freedom Center did not stand a chance.

When I called Ms. Burlingame on Wednesday, the day Gov. Pataki put a stop to the Freedom Center, she sounded contemplative, not triumphal. "We're not really done," were her first words--the Freedom Center may have gone, but it was still not certain what would take its place. She wanted the recognition of her victory to be restrained, not raucous, and her voice betrayed some of the fatigue that can so often set in as soon as a battle of attrition is over. I suggested that we meet the next morning, to talk about the turn events had taken.

"Oh no!" she protested, "Not in the morning! I look horrible in the morning!" This last assertion turns out to be the only thing I've heard her say that is open to refutation.

At 10 a.m. the next day, I found her outside her home in Pelham, N.Y., in prosperous Westchester County, looking the very picture of blond, suburban poise: neat hair, pearly teeth, understated jewelry, crisp white cotton shirt, laundered blue jeans, blue flip-flops, pink toenails. She was hauling empty garbage cans off the sidewalk and back onto her drive, where her SUV was parked. Two dogs barked their greetings as we stepped into a house so immaculate that it was hard to believe it was kept not by a Full-time Homemaker, but by a Full-time Activist.

" 'Activist'. . . I'm not entirely happy with the term," she said to me with mild reproof. "I'm a citizen." We were seated in her small office--a place where Mexican oil paintings vied for space with pictures of her brother and a collage of yellow Post-it Notes on the wall. This was, in fact, the one part of her house that was less than perfectly ordered; I confess that I was reassured by this--Ms. Burlingame, disconcertingly, can come across as a seemingly flawless person on a seemingly flawless mission.

This was not the view, of course, of the men she took on at the Freedom Center. "They dismissed me as a Westchester housewife," Ms. Burlingame said, more in mirth than in indignation. She was referring, principally, to Tom Bernstein, the center's chairman, best known before this project as a founder of Manhattan's Chelsea Piers leisure complex. Mr. Bernstein led a triumvirate, along with Peter Kunhardt (the creative director of the center and a filmmaker of repute) and Richard Tofel (the president and COO of the center, and formerly the assistant publisher of The Wall Street Journal), that sought to derail Ms. Burlingame's opposition to the Freedom Center.

"When I talked to Tom Bernstein in person about what they were about to do at the center," Ms. Burlingame recounted, "he said to me, 'You know, 9/11, if we don't put it in a broader context, it will be forgotten. It will not stand the test of time if we do not put it in a broader historical context.' The arrogance of this was stunning. And when I told him that Ground Zero was, to the 9/11 family people, and especially the military, a sacred place, and that you cannot put anything on this site that ignores that, denigrates that, marginalizes that, or does not give it the acknowledgment that is due . . . he looked at me blankly. Completely blankly. They were trying to cut 9/11 out of it completely."

So is there no broader context for 9/11? "Absolutely!" she exclaimed, chafing mildly at the idea that she might have come across as one-dimensional. "Of course there is! But one of the challenges of putting together a memorial museum is doing it in real time. This history is still unfolding. We have these people who are still at large, not the least of whom is Osama bin Laden.

. . . So when people say, 'Hurry, hurry, hurry, and build this,' I say, 'Why? We still don't have a grasp on the full story here.' "

Here, Ms. Burlingame resorts to her greatest strength--forensic rigor acquired at law school (where she went, at the age of 37, after working for TWA as a flight attendant for several tedious years): "You can't tell the broader story of 9/11 and not talk about terrorism, or Islamo-fascism, or the jihad. . . . But in the Freedom Center's 49-page report they never once mention bin Laden. The words 'al Qaeda' never appear anywhere in it. There's nothing about the war on terrorism."

This is the woman Messrs. Bernstein and company dismissed as a hausfrau. How they did so is baffling: She has the facts at her fingertips, the confidence of a person at ease with authority, and the rhetorical skills of one at home with the language. How could they have believed that she would just go away? "They were ambitious," Ms. Burlingame replied, "and myopic.

Bernstein is an ideologue, a true believer. He told me that he was prepared to dedicate the next 10 years of his life to the center." They patronized her: By her account, Mr. Bernstein said, "Debra, we're calling on people from all sides of the political spectrum . . . very balanced . . . people who are very dignified." To which she responded, "Oh really! Tell me who you have that's conservative. And he replied, 'Fareed Zakaria' [editor of Newsweek International]. I squinched my face up and said, 'He's not conservative,' and Bernstein goes, 'Naah . . . he's not, yeah, you're right, he's not.' "

This gets to the heart of the problem: The Freedom Center's progenitors were convinced--utterly and adamantly--of their own reasonableness. In an inversion of the usual conditions of passion, the Forces of Rage--here, led by Ms. Burlingame--had an impressive clarity of vision; by contrast, the self-styled Forces of Reason were blinded by their own certitudes. (Ms. Burlingame insists that the blind include the editorial page of the New York Times, which twice attacked her by name--describing her, even, as "the Governor's Proxy"--yet did not consider it important to print a letter from her in response. The page's editor, Gail Collins, would not, it seems, take her calls. "A very, very snotty assistant said to me, 'Let me take your information.' Ms. Collins was 'busy,' 'unavailable' . . .")

Finding interlocutors on the telephone wasn't always this hard for Ms. Burlingame. After her op-ed appeared in the Journal in June, she received calls from political players in Washington, asking her to drop her opposition to Mr. Bernstein's project. She is prepared, only, to name John Bridgeland--a former director of the Domestic Policy Council in President Bush's White House, deputy policy director for the Bush-Cheney 2000 campaign, and, after 9/11, the first director of the USA Freedom Corps Office. He called twice "to discourage me . . . no, not discourage, to 'explain what was actually going to be happening [at the Freedom Center],' and that I'd 'got it all wrong.' I said to him, 'Are you aware of some of the exhibits that they're talking about?' " He wasn't. "Here's a man who didn't know what was happening, yet he was picking up the phone and trying to effect an outcome."

Ms. Burlingame's face, never inscrutable, reflects afresh some of the fury she must have felt at the time. Composure is only a part of her arsenal. "Anger can be very, very productive, as long as it's focused and you don't lose your mind. After the London bombings [in July], someone asked me, 'Have we become complacent? Do you miss 9/11, when people had more unity?' And I say, 'No, no, no. What I miss is the anger. And the clarity. That's what I miss.' "